Mei Xin Wang

Mei Xin Wang is China Resource Specialist at the Department of Asia at the British Museum. She has an MA from SOAS in Chinese Art and Archaeology. Her research interests are in Chinese seals, Chinese lacquer and early 20th century Chinese ceramics. Her conference paper, Chinese Seals as Status of Power, was published in the British Museum Research Publication in 2018.

Lacquer box (Cuan He 攢盒)

Black wood with red, green, yellow, brown lacquer and gold foil

Zhejiang province, China

2017

Diameter: 35cm, height: 13cm

2017,3043.1

This red lacquer box was commissioned by the British Museum to form part of the contemporary collection displayed in the Sir Joseph Hotung Gallery of China and South Asia at its reopening in 2017. It was designed by Jiang Qiong’er 蔣瓊耳(1976 – ) and made by Master Gan Erke 甘爾可 (1955 – ) in China.

The technique used to make this box is called Xipi laquer犀皮漆 or ‘rhinoceros skin lacquer’ developed from the filled-in and inlaid method. It differentiated from other types of lacquerwares because of its luminous and silky exterior and its irregular and unpredictable patterns on the surface. Earliest known lacquerwares made in this technique are dated to the 2nd century AD from the tomb of General Zhu Ran 朱然 (AD182-249). Although continuously used to produce lacquerwares in the following centuries, the technique was discontinued from the 19th century until Master Gan Erke 甘爾可 revived it in the early 21st century and instilled an innovative variation by applying gold foils over red, green, yellow and brown lacquers on the surface to render a glowing golden sheen.

In the centre of the cover of the box is a rock-shaped handle made of agate. Inside are six trays made in black lacquer. A two-line inscription is imprinted in gold inside the cover with marks of the maker and the designer on the base.

Boxes of this type are traditionally called Cuan He 攢盒in China and used to contain an assortment of dried fruits during festivals and celebrations.

It is on display in G33 at the British Museum in the 21st century case.

Seal with knob in the shape of a lion dog

Material: quartz

17th century

H 5.80cm x L 2.7cm x W 2.7cm

Bequeathed by Sir Hans Sloane

SLMisc.898

On display in G1 at the British Museum

With a two-character inscription hufeng護封, ‘Sealed Herewith’, carved in relief on the base, this seal combines both functionality and an aesthetic beauty unique in Chinese seals. It could have been used to seal a letter but would also have been a valuable object on the scholar’s desk as well.

Seal with knob in the shape of a tortoise

About 3rd century AD

H 3.2cm x L 2.4cm x W 2.4cm

Purchased from George Eumorfopoulos

1936,1118.200

On display in G33 at the British Museum

This seal would have been given to the Duke of the Outer Region in the Han dynasty (202BC – AD220), as is shown in a four-character inscription on the base 關外侯印guanwai houyin, and would have been carried by him at all times to symbolize his authority. The material used, gilded bronze, for an official of this ranking was specified in the ancient hierarchical system in China and the tortoise carries symbolic meanings of wisdom and longevity.

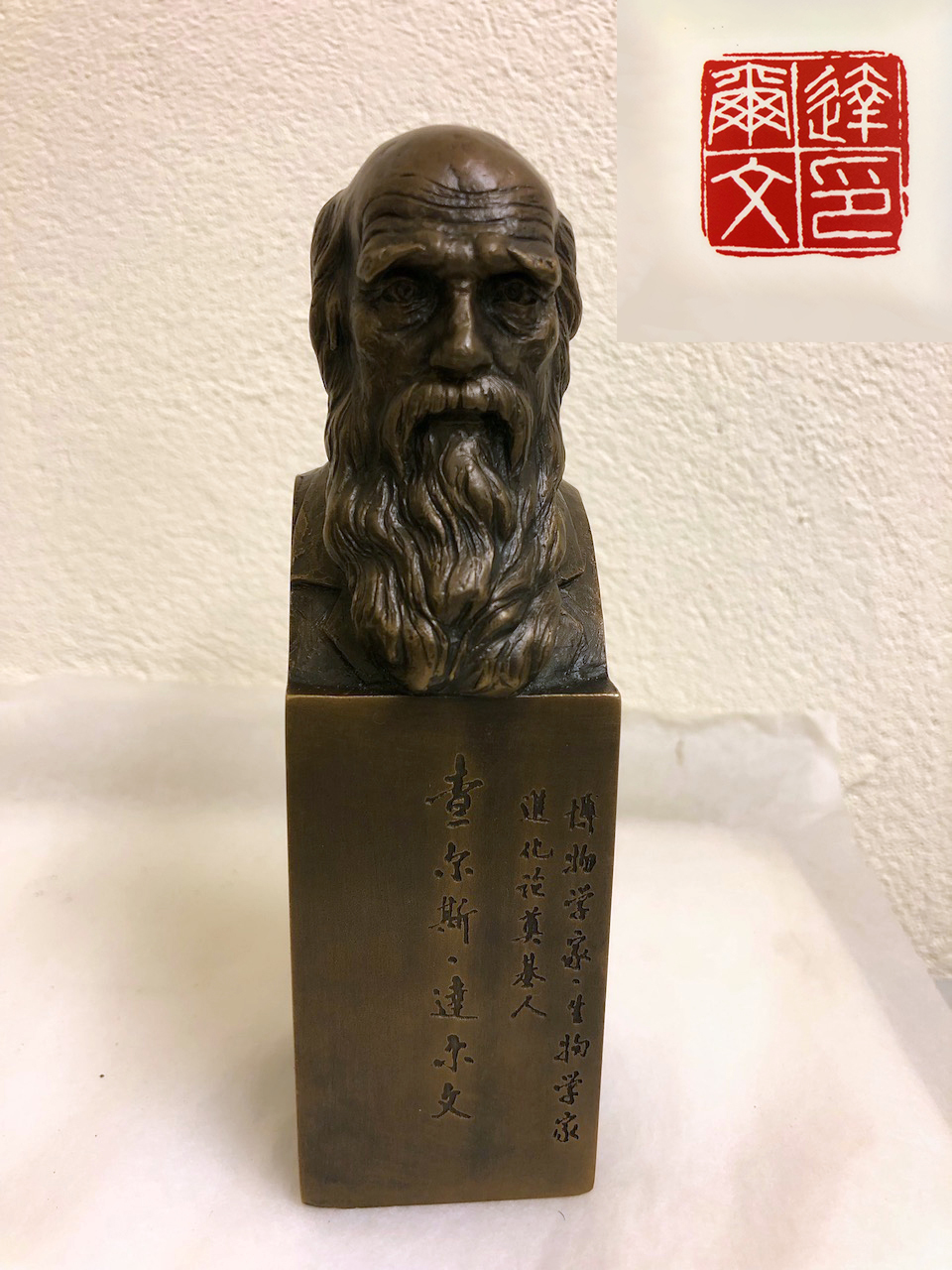

Seal with knob in the shape of the bust of Charles Darwin

2011

H 14.7cm x L 4.3cm x W 4.3cm

Donated by Li Lanqing

2012,3045.3

https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/A_2012-3045-3

This brass seal serves as a mini statue of Charles Darwin. On the base is a four-character inscription Daerwen yin 達爾文印, ‘Seal of Darwin’. It is a modern day representation of what Darwin’s private seal might have looked like in Chinese.

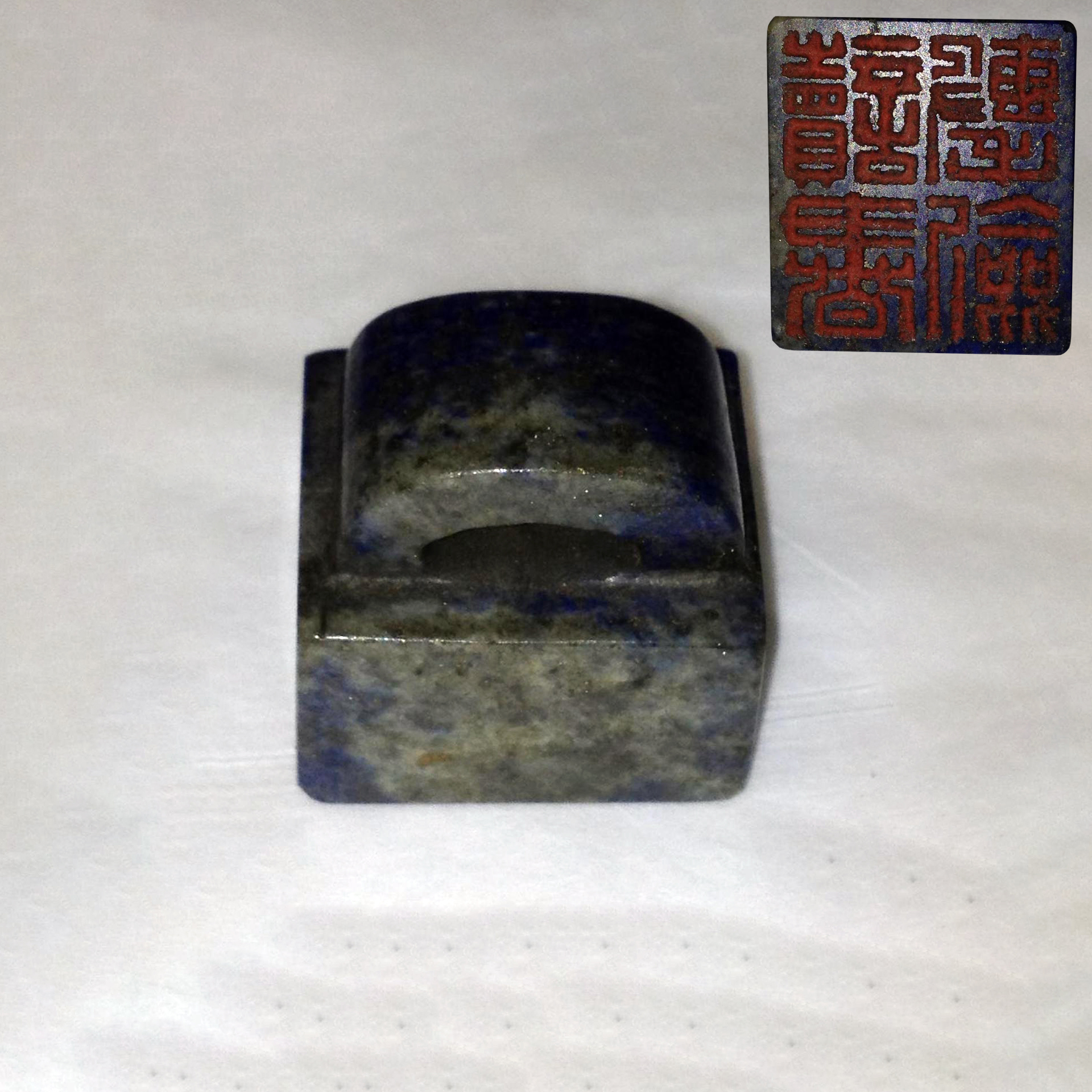

Jade seal with tile shaped knob

Material: jade

Early 19th century

H 2.5cm x W 2.2cm x L 2.5cm

Donated by Sir Augustus Wollaston Franks

1885,1227.68

https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/A_1885-1227-68

The inscription on the base of this seal, ‘Reading and swordfighting’, or dushu jijian 讀書擊劍, reflects the favoured daily activities of the owner. The choice of the tile shaped knob, a form that was often seen on Chinese seals in the Qin and Han dynasties (221 BC – AD 220) in China, shows the popularity of antiquarian studies among the Chinese scholars in the second half of the Qing dynasty (1644 – 1911).